Signs say a lot about place.

When I return to Auckland after a long spell on the island, I’m aware of the insistence of signage.

I can’t help myself from reading them and by the time I get to my house I often feel intruded upon, messed with, preached at and on edge.

I like the way the island has few pretentions with its signs.

The island feels like stepping back in time, visitors often say.

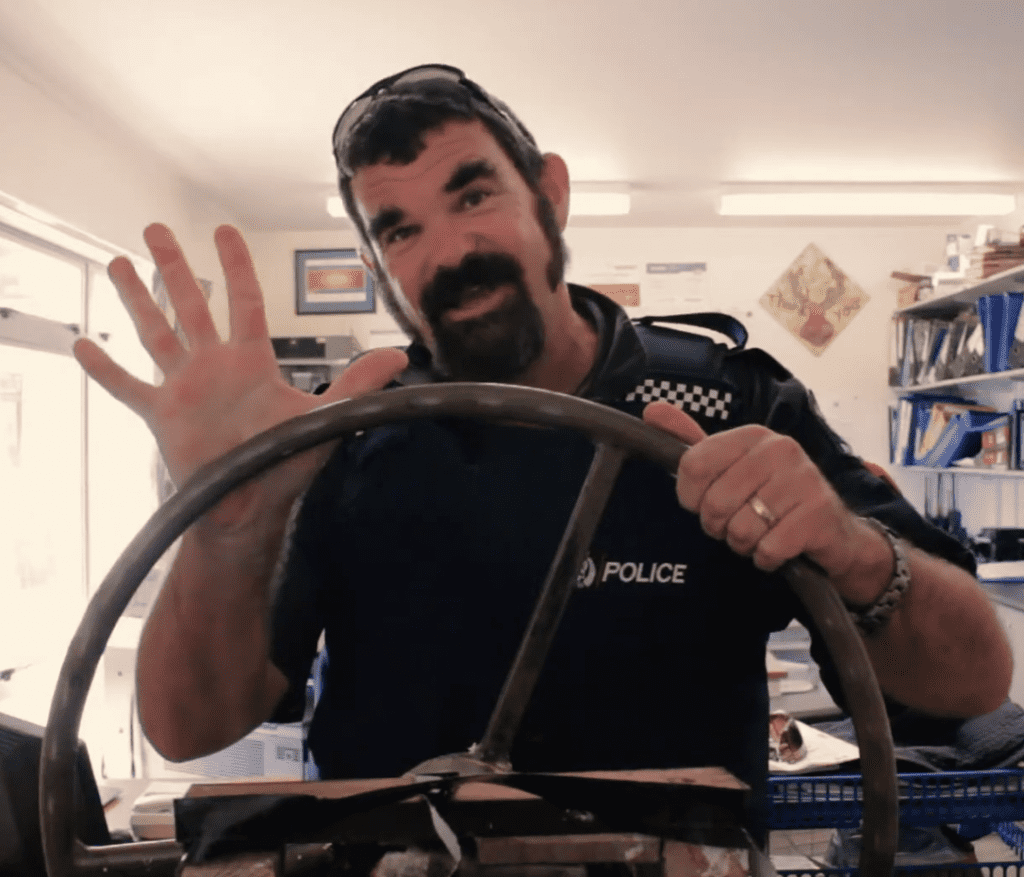

One reason is because people make time to wave.

Island policeman Roger Bright says “99.9999 percent of people wave” and after a while tourists do the same.

There’s a series of instructional videos showing how it’s done for those that have forgotten – www.youtube.com/watch?v=r97pMmTn71c

I’ve spent the past month in a part of the country that pioneered slow tourism and have taken the opportunity to ask a few locals what they’ve seen and learned since New Zealand’s original cycle trail was created.

Ken Gillespie farms just south of Ōtūrēhua on the Otago Central Rail Trail. He is on the rail trail trust as well as committees that have organised local curling competitions and the brass monkey motorcycle rally.

When the railway line between Middlemarch and Cromwell closed in 1990, one his neighbours saw the opportunity to do more than return the land to adjacent farmers as had been proposed.

The Otago Central Rail Trail Charitable Trust was formed to raise funds for development and provide volunteer input, in partnership with the Department of Conservation which owns and maintains the track.

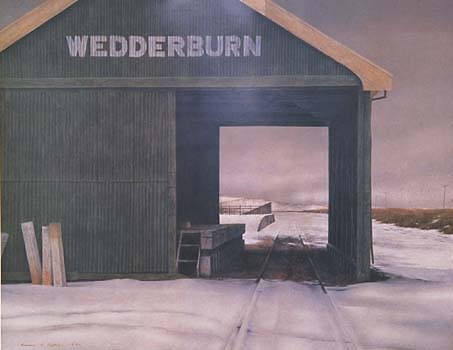

Work has included re-decking bridges, and installing signage, interpretation panels, toilets and shelter sheds along the trail, improving the surface of the old railway to give cyclists a smooth ride, and preserving railway heritage, such as the Wedderburn Station goods shed made famous by local painter Grahame Sydney.

“We’ve built up the infrastructure as the trail has grown,” says Ken.

Today around 15,000 people bike the full 152 km trail each year, usually in three to five days. The average age of cyclists is 57 years old and the popularity of electric bikes – often hired from business along the trail – looks set to push this higher.

The trust’s biggest fundraiser is a passport, with cyclists adding stickers for each place they visit.

Ken runs guided tours of the Hayes Engineering Works, a popular stop on the trail, where windmills, fencing, shearing and pest control tools were manufactured and patented to service local farms and even overseas markets.

“Hold on to your heritage and be prepared tell people if you think they are not doing things right,” Ken advises, “authenticity is everything.”

Bill May runs The Crow’s Nest Backpackers, set up when the trail opened in 2000, from the original homestead associated with Gilchrist’s Store – also a museum – just along the street. First a couple of rooms were added above the garage and then as the trail’s popularity grew it has expanded to bunkrooms, cabins, the bach, a house truck, a converted car transporter, tent sites and spots for motorhomes.

Bill has watched as the historic pubs along the trail have “spruced themselves up and improved their menus.”

In many respects Aotea offers the equivalent of the Otago Central Rail Trail, with its two-to-three-day Aotea Track giving access to historic bush tramlines and dams used to extract kauri logs and the island’s rich native fauna and flora.

A couple of extra days can take in sites and stories associated with the island’s mana whenua Ngāti Rehua Ngātiwai ki Aotea, gold and silver mining, farming, shipwrecks, and whaling, as well as many beautiful beaches.

The island’s dark sky and nature guiding businesses and its festivals – which celebrate off-grid living, music, gardens and ‘big ideas’ – have all been developed and are organised by locals.

The island provides an eclectic and comfortable mix of accommodation; hospitality provided by clubs, a pub, cafés and restaurants; and a homegrown range of pottery, artwork, books, beer, gin, honey and beauty, health and rongoā products.

Destination Great Barrier Island Chair Derek Bell sees the Otago Central Rail Trail as a great model for the island – “active tourism that is run by small local operators, with the rewards going straight back to the community.”

Before moving to the island, he drove regularly between Dunedin and Queenstown along the Pigroot.

“The Maniototo is the only other place I’ve been where everyone gives you a wave.”

Written by Tim Higham, with the support of Destination Great Barrier Island.