Kākā at Glenfern, photo by Stuart Farquhar

The island’s environmental trust turns 20 this month and friends and supporters are invited to celebrate its successes at a birthday party at Glenfern Sanctuary.

The Aotea Great Barrier Environmental Trust (formerly the Great Barrier Island Charitable Trust, then the Great Barrier Island Environment Trust) has been a strong voice for conservation since formation, its Environmental News (available at https://www.gbiet.org/environmental-news-archive) an important record of the island’s biodiversity value and issues.

“There’s nothing of conservation significance that’s happened on the island that it hasn’t been covered since 2002,” says current AGBET chair Kate Waterhouse; a history that includes advocacy for marine reserves, world heritage and conservation park designation, rat eradication on Rakitū, the plight of threatened fauna and flora, a significant State of the Environment Report in 2010, the transfer of Glenfern into public ownership as a regional park, and always the case for greater recognition and investment by central and local government.

It is easy for visitors who see a mohu-pererū/ banded rail on the roadside, kākā in the pohutukawa or pāteke in a creek, to assume all is well on an island without stoats or possums, but the trust conservatively estimates there are a thousand feral cats and a quarter of a million rats in Aotea’s forests at any one time, killing 80,000 birds annually.

Founding trustee John Ogden says when the trust was formed, he expected there wouldn’t be a rat left on the island in 20 years. “It was so bleedingly obvious, the difference this would make to the birdlife and the forest.”

But John – a retired associate professor – admits now he is an ecologist not a social scientist and finding a path to share the trust’s vision of a rat and cat free island and convince the community and government that it is feasible has been a difficult road at times.

Kate Waterhouse says the trust’s purpose has remained the same – “to create understanding of the value of what we are trying to look after” – but “the context has completely changed.”

“The focus is no longer on the how, but the why and the who.”

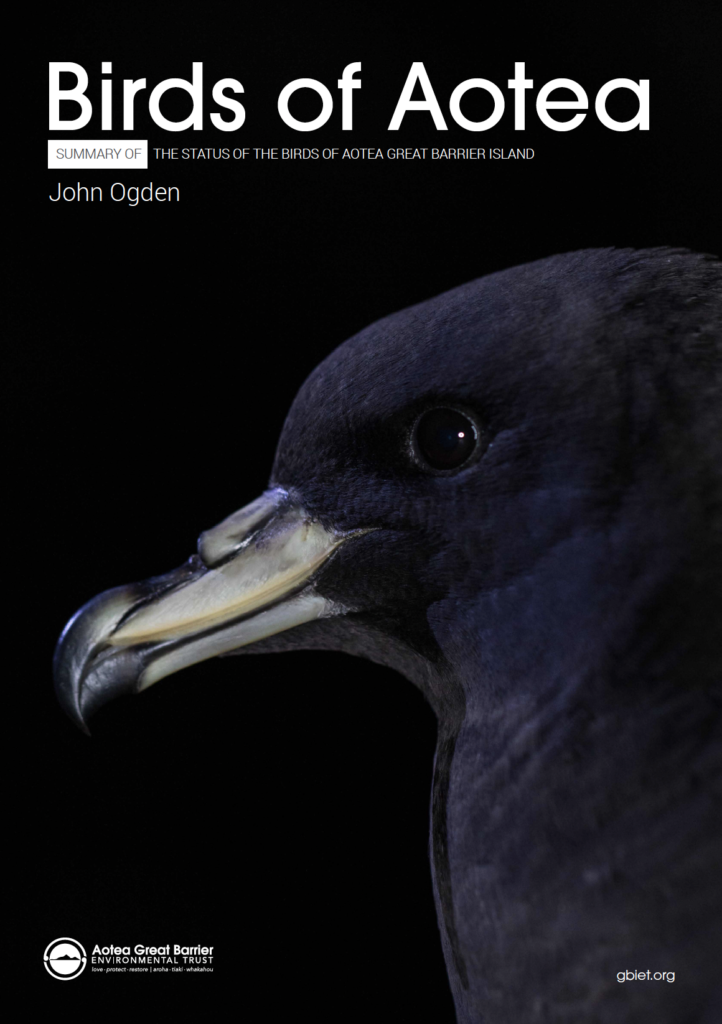

Fittingly, the anniversary will see the launch of a new report, the Birds of Aotea with John Ogden as its lead author.

A tākoketai/ black petrel graces the cover of Birds of Aotea. Image Shaun Lee.

The report shows 11 species have become locally extinct since the first list of birds was made by Frederick Hutton in 1867, including the forest birds kōkako, hihi/stitchbird, pōpokotea/whitehead, kākāriki/yellow-crowned parakeet, and tīeke/ saddleback. Eighteen introduced species have arrived on the island over the same period, mainly taking advantage of farmed and settled areas.

Others close to disappearing include the titipounamu/rifleman, miromiro/tomtit, kākāriki/red-crowned parakeet and the reintroduced toutouwai/North Island robin. The cloud forest of Hirakimatā is particularly important for these species, as well as for the largest colony of takoketai/ black petrels – otherwise only found on Hauturu/ Little Barrier – and a small population of tītī / Cook’s petrels.

Significant wetlands at Whangapoua and Kaitoke support populations of pārera/ grey duck, matuku-hūrepo/Australasian bittern, pūweto/spotless crake, moho pererū and mātātā/fernbird, all nationally in decline. Of particular concern is the pateke/ brown teal; its island population slumping from 1200 birds in 1996 to 400 in 2021. While feral cats and rats are likely to be a factor, the report says further research is needed.

Birds of Aotea reiterates the importance of the island for seabirds, with relict populations of tākoketai and tītī, ōi/ grey-faced petrel, pakahā/ fluttering shearwater and kuaka/common diving petrel.

Being central to the wider Hauraki Gulf region – which with 27 has the highest number of breeding seabird species in the world – Aotea’s potential for restoration has been internationally recognised. Rakitū is an important beginning, since rats were successfully removed in 2018, with opportunity for both reintroductions and natural recolonisation. However, the report suggests a restoration and management plan is urgently needed for the island.

Beaches, estuaries and rocky fringes are important places for tūturiwhatu /New Zealand dotterel and tōrea/variable oyster catcher, waders, migratory birds like the kuaka/bar-tailed godwit, kororā/little penguins, gulls, shags and the Hauraki Gulf’s largest colony of takapū/ gannets.

AGBET’s new poster shows the richness of Aotea’s bird life, www.gbiet.org/shop-merch.

Kate Waterhouse says the range, complexity and continuum of habitats – from maunga to moana – creates a richness and biodiversity of biota that is often missed in rankings based on individual species and ecosystem types, used to guide national funding priorities. “DOC manages 60 percent of the island but has been massively under-investing for years,” a situation she hopes will change under the proposed National Policy Statement on Indigenous Biodiversity.

The Birds of Aotea report says 23 years of predator control and dedicated monitoring at Windy Hill have proven beyond doubt the devastating impacts of rats and the huge difference sustained predator control makes to the number of tūī, kererū and kākā, lizards and wētā.

While forest is regenerating at pace around the island, high numbers of rats mean fruit bearing trees like taraire, pūriri and kohekohe are not part of this succession. This also effects its resilience to withstand forecast climate change, with the presence of invasive species like pine making it increasingly prone to fire.

Judy Gilbert, one of the trust’s founding trustees and long-time manager of the Windy Hill sanctuary – which now covers 800ha of private land with 18 owners – is surprised that the tools to control predators are essentially the same as when she started her work, despite significant investment in research and development. Now approaching her 70s, Judy sees the island pest management mahi being taken up by new coalitions of landowners, community groups and agencies.

School children release robins at Windy Hill with Judy Gilbert in 2004. Locally extinct toutouwai were reintroduced to Glenfern and Windy Hill sanctuaries in 2004, 2009, and 2012 and have established a breeding population on Hirakimatā. High rat numbers have prevented further translocations of lost birds back to the island. Photo by John Ogden.

The trust has helped spawn a raft of new initiatives; the Aotea Trap Library which now loans out over 3,000 traps in a community of 435 households, the Ōruawharo Medlands Ecovision group which hosts weekly working bees and is currently working to expand its efforts to join up with Windy Hill, and the annual Aotea Bird Count, helped by grants from the Aotea Local Board, Auckland Council, Lotteries Commission, Foundation North and DOC.

And perhaps most significantly, the Tū Mai Taonga project – championed by both the Aotea Conservation Park Advisory Committee and the environmental trust and now being led by Ngāti Rehua Ngātiwai ki Aotea – which has begun removing feral cats from Te Paparahi and rats from smaller offshore islands. Backed by DOC, Auckland Council, Predator Free 2050 Limited and informed by tikanga and learnings from other large landscape projects, it is part of a long-term, integrated effort to make the island predator-free.

Members of Ōruawharo Medlands Ecovision on a recent visit to Awana. Photo Lotte McIntyre.

Kate Waterhouse is optimistic that in another 20 years we will have worked out how to live sustainably on Aotea, helped by the strong focus on nature in schools and kura.

“I’d like to think we will hear kōkako and the calls of seabirds overhead at night, see the flashes of pink and blue shoals of maomao in the sea and the mushrooming headings of strong trees in the forest, and perhaps some of the aunties will be saying ‘yes, we are back to the old ways’”.

The birthday party is on Saturday February 11 at Glenfern Sanctuary from 1-5 pm, with Dame Juliet Gerrard, past and present trustees, the island’s kaitiaki and conservation community. Anyone interested to find out more about the Aotea Great Barrier Environmental Trust’s legacy and vision is invited.

RSVP to contact.gbiet@gmail.com.

Written by Tim Higham, with the support of Destination Great Barrier Island.