Visitors to the West Coast bays of Aotea may have noticed they have company.

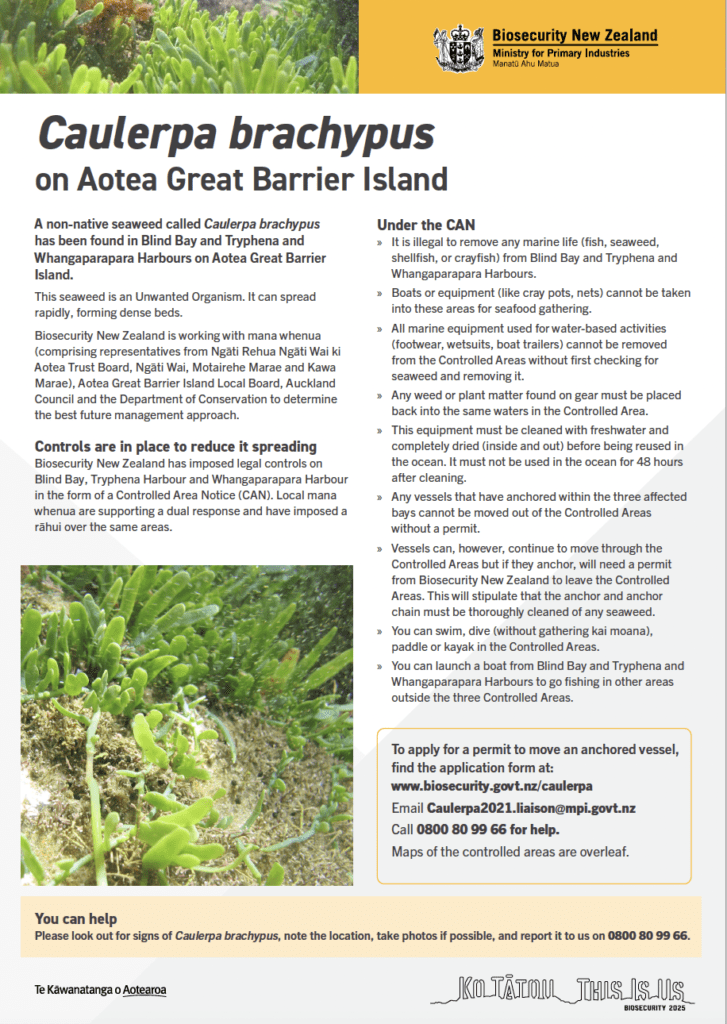

Carved figures or pou appeared shortly after the discovery of exotic Caulerpa brachypus seaweed in island waters as symbols of the concern and care of Ngāti Rehua Ngātiwai ki Aotea.

Pou at Rangitāwhiri (Tryphena) – Ben Mason

Resident mana whenua initiated the rāhui tapū to coincide with the Ministry of Primary Industries’ Controlled Area Notice designed to minimise the spread of the invasive tropical seaweed.

Rodney Ngawaka was part of a small party that blessed the pou before sunrise earlier this year. He says rāhui tapū have traditionally been used by Māori to mark territory, close an area after a drowning, or allow the mauri of an area to replenish.

The pou signify the long occupation and kaitiaki by mana whenua of these places and the stories embedded in them, at Rangitāwhiri, Ō-Kupe-Mai-Tawhiti, Whangaparapara and Te Whanga-o-Rarohara.

The presence of Caulerpa means that anchoring without a permit, fishing and taking of seafood from Rangitāwhiri/ Tryphena Harbour, Ō-Kupe-Mai-Tawhiti/ Okupu or Blind Bay and Whangaparapara is currently prohibited.

The seaweed can quickly spread when broken by wave action, anchors or fishing gear, can survive a week out of the water if in a moist location like a fishing net or anchor rope, and forms vast, dense beds or meadows, smothering other native life.

Aotea is the first place the seaweed has been discovered in New Zealand and is thought to have been brought here on an international vessel. A second infestation has been found on Ahuahu/ Great Mercury Island, also subject to a closure.

The seaweed has become a problem in other harbours around the world and the rāhui is enabling the Ministry of Primary Industries to consider options for its control in consultation with mana whenua and the community.

Another form of rāhui can be applied under Fisheries Act regulations and recently an island-wide rāhui was initiated around Waiheke restricting the taking of kutai/ mussels, koura/crayfish and tipa/ scallops. The closure under section 186A of the act for two years was approved by the Ministry of Fisheries to allow stocks to recover.

Pou at Ō-Kupe-Mai-Tawhiti (Okupu) – Sonya Williams

A similar closure halted scallop harvesting off the Coromandel after concerns and an application by Ngāti Hei in 2021.

A decision this year by the Minister of Fisheries closed recreational and commercial scallop fisheries in Northland, the Hauraki Gulf and Coromandel from 1 April, but left two areas around Hauturu/Little Barrier Island and the Colville Channel off Aotea open.

The exemption has disappointed many. Scallops are mass spawners and large undisturbed beds are important for replenishment.

Both Ngāti Manuhiri, a hapū of Ngāti Wai based at Pakiri, and the Motairehe Marae Trust have applied for section 186A rāhui to protect tipa around Aotea.

The Motairehe application also covers koura and pāua which have declined markedly around the island. Crayfish are considered functionally extinct, meaning they can no longer play their important role as predators in the ecology of rocky reefs.

In recent years many shallow kelp-covered reefs have been lost to kina, which increase in number when too many of the large crayfish and snapper that predate them are removed.

The marae trust has initiated community discussions about its proposed rāhui and the broader opportunity to manage fisheries and protected areas locally in a new approach called “ahu moana”.

Ahu moana emerged from the three-year Sea Change collaborative process, following state of the environment reports by the Hauraki Gulf Forum which showed marked declines in many fish stocks and environmental quality.

The Department of Conservation and Ministry of Fisheries have pledged support to a pilot the creation of an ahu moana area around Aotea if there is sufficient interest and support for co-management by mana whenua and the community.

There’s an emerging code of conduct among island fishers – take only what you need, release big breeding fish, don’t use scallop dredges, or set nets on reefs.

Islanders appreciate it when visitors respect these ways.

The presence of pou on the headlands of the bays of Aotea is a sign that our marine environment is changing and there’s an appetite for doing things differently and better by the environment here.

Written by Tim Higham, with the support of Destination Great Barrier Island.