I’m sitting on the veranda of what was once the villa homestead on a 400-acre farm running down to the beach at Mulberry Grove, near where the ferry arrives.

Derek Bell bought it on a sub-divided acre in 2005, then a few years later put in an offer on the farm block behind it.

Eighty five percent was in regenerating bush and under a QE2 covenant with the bottom 40 acres in pine forest, which he viewed as “a blot on the landscape.”

Up for a challenge, Derek employed forestry consultants to fell the trees, truck them to the wharf then barge them back to Auckland – the first timber to be exported from the island since kauri logging days.

But the price he got for the logs barely met the cost of transportation and the slash took three winters of permitted fires to burn.

His first native trees cost 19c each to get from Tutukaka to Auckland then $1.60 each from Auckland to the island, so Derek set up a native plant nursery in an old four-berth milking shed; a joint effort with the Windy Hill Rosalie Bay Catchment Trust, which controls predators to create a wildlife sanctuary across 18 neighbouring properties.

He’s planted several thousand trees from the nursery, which now also supplies other island restoration efforts.

To balance the books, he adjusted five existing titles on the farm block to create acre sections with views off Rosalie Bay Road.

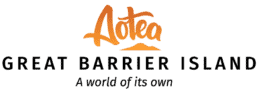

“I’ve been referred to as ‘that Queenstown developer’,” says Derek. He’s a former GP and medical specialist in environmental health and infectious disease control for Otago and Southland who retired to live on the island at 59 and has a passion to look after the streams and forests of the valley he shares with others.

As current chair of Destination Great Barrier Island he’s keen to see the island develop its own kind of “slow tourism”, one that allows visitors to meet residents and experience the place and its culture in a way that contributes to local values and livelihoods.

Alan Phelps runs another nursery, near Ōkiwi in the north.

Currently he’s growing 25,000 plants – kahikatea, titoki, pūriri, mānuka, tī kōuka/ cabbage trees harakeke/ flax and others – for the wetland behind Ōruawharo/ Medland Beach.

Around 350,000 will be needed to restore the drained, rush-filled paddocks currently trampled by wild cattle and pigs to their former glory. The owner of the block plans to fence the wetland, recreate a meandering stream and put in boardwalk so the public can experience its transformation.

Alan’s planting efforts began during a 19-year stint as a farm manager at Nagle Cove from 1988, watching as eroding farmland silted up scallop beds after heavy rain. So, he set up a nursery and put in trees along a 100-metre riparian strip around the bay.

He then helped Tony Bouzaid get planting in the early days of the Glenfern Sanctuary, has been helping restore privately-owned Motuhaku island near the entrance to Port Fitzroy and planted 30,000 trees – now a forest – for a Palmers Beach landowner.

The former-shearer spent four years working for council advising farmers on fencing and planting around the Kaipara harbour – some who keep in touch to tell him how much it has improved their operation and bottom line – but is now happiest “reducing his footprint” and contributing here.

He’s inspired by the Country Calendar TV programme which shows the variety of uses people are putting their land to. He runs a small herd of milking sheep and would like to see all animals grown on the island eaten here. He and his partner ran a popular café and meeting place in Ōkiwi and he’s recently converted it to the Motu Honey House B&B, “which has been glorious”.

There’s no shortage of work for those who have a passion, he says.

Alan is a natural connector. “People like to be part of something – and appreciate a bit of direction.”

He sees the island’s future as a conservation park to which many landowners contribute “their bits and pieces”.

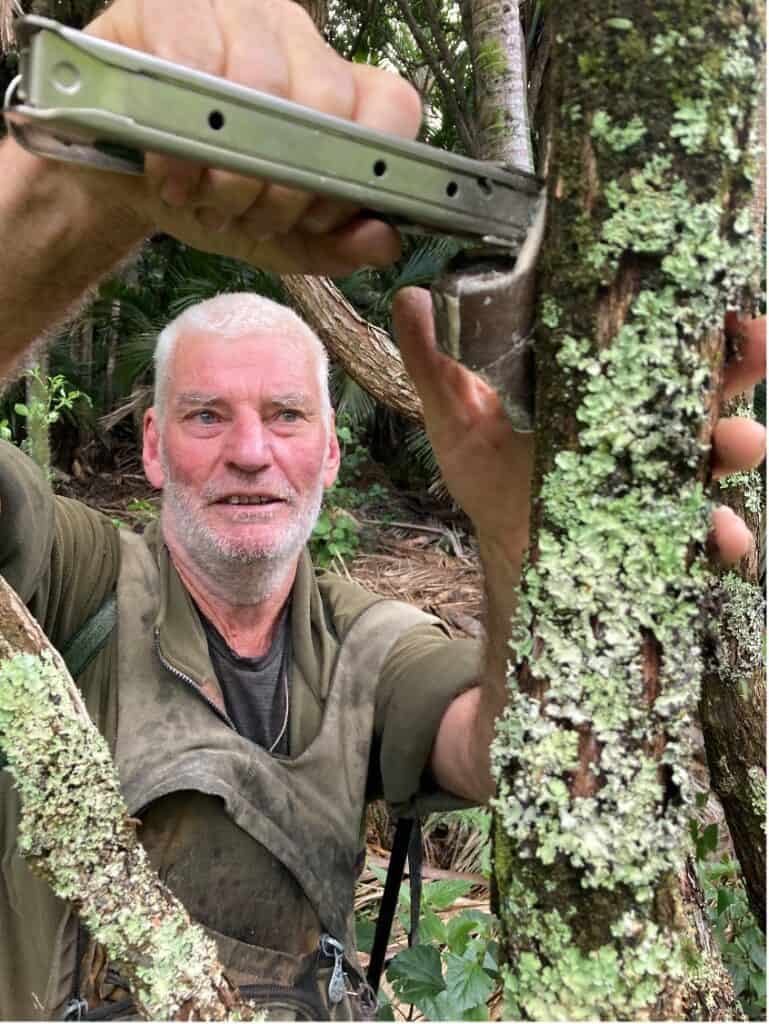

Murray Staples is doing his bit to help 120 landowners knock down the rats that plague the island’s forests.

He’s developed a cost-effective method using waxed toilet rolls filled with rat bait stapled to tree trunks at shoulder height and can lay a 100 over a kilometre in a morning.

He has “a cup of tea and a rest and makes up gear for the next day.” Residents assist by leaving toilet rolls in a blue “Rat A Tack” barrel at the top of his driveway on the summit of Tryphena hill. He fills them with a paste made from diphacinone, a rat-specific, biodegradable toxin, and food grade peanut butter.

They last for several months and when rats move into an area they get “smashed.”

He reckons he’s removing 15-20,000 rats a year from over 1,000 hectares and his loyal client list keeps growing.

Murray came to the island in the Eighties from the King Country after a career in the army and “couldn’t believe the size of the trees on the land I bought for $15,000. I started trapping rats at home and just carried on.”

He says more and more people are going to come to the island so there needs to be rules around pets. “Bird averted dogs and no cats – there’s no such thing as a totally pet cat – beyond that I don’t care.”

Recently, the electrics in the motor on his cruising yacht “Freedom” failed and he had to sail into Tryphena harbour in very light wind.

“I could hear all this bird song from the trees ringing the bay that I’d never noticed before. I thought that’s the reward of the efforts of many people over the last 10 years.”

Written by Tim Higham, with the support of Destination Great Barrier Island.