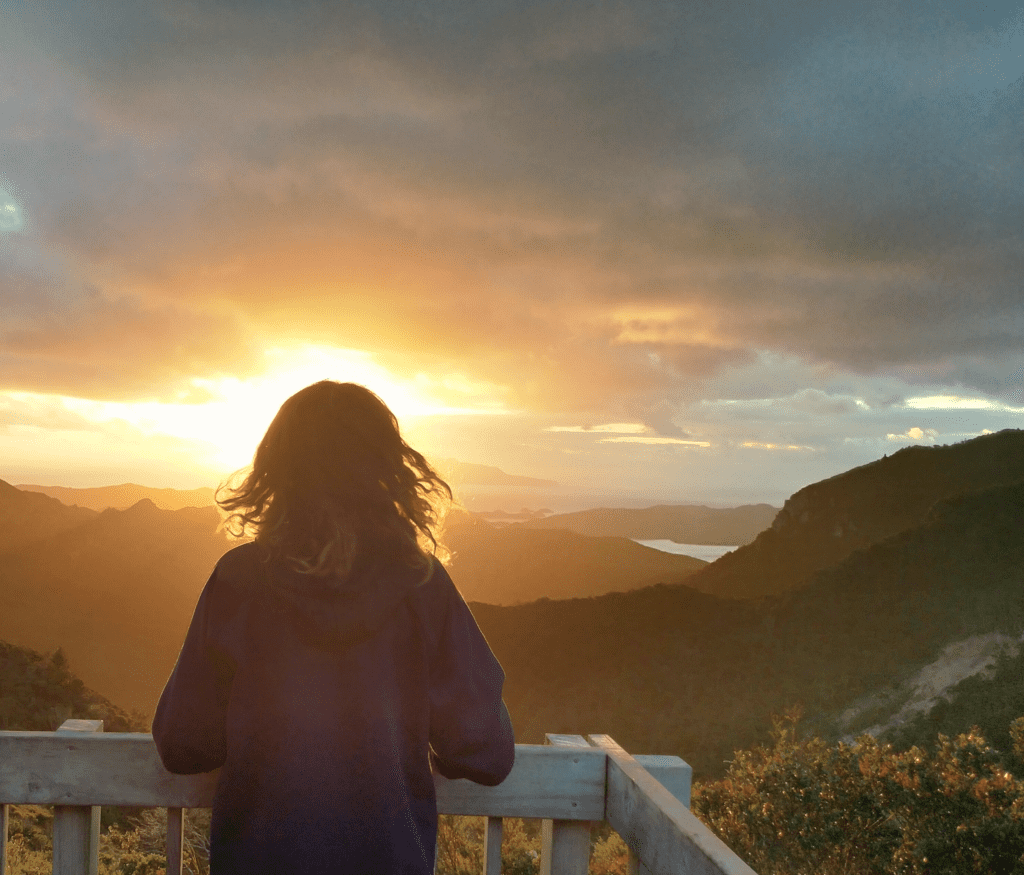

From the deck of the Aotea Track’s Mt Heale (Matāwhero) Hut the vista at twilight is awe-inspiring.

It faces west towards Te Hauturu-o-Toi / Little Barrier Island. To the left is the distant glow of Auckland.

Ecologically, Aotea Great Barrier Island sits in the middle ground between them.

The hut is surrounded by the largest nesting population of tāiko (black petrels) in the country or tākoketai as they are known to Ngāti Rehua Ngātiwai ki Aotea.

The mainland has lost these ocean-wandering seabirds, to stoats, rats, feral cats and pigs and habitat destruction.

Te Hauturu-o-Toi has the only other tākoketai colony. Birds that were recorded by Europeans on Aotea but are now absent include the extinct koreke (New Zealand quail), tūturuatu (shore plover), hihi (stitchbird), tīeke (saddleback), koitareke (marsh crake), kōkako, popokatea (whitehead), pipipi (brown creeper), tītipounamu (rifleman), yellow-crowned kākāriki, tītī (sooty shearwater) and kuaka (common diving petrel). The tuatara, pekapeka (short-tailed bat) and pūpūharakeke (giant land snails) have also gone.

Some of these species survived on, or been translocated to, predator-free Te Hauturu-o-Toi, including offspring of the last two kōkako from Aotea, removed in 1994 to save them from rats. Te Hauturu-o-Toi is now among the country’s most valuable nature reserves, subject to a conservation management plan agreed by Ngāti Manuhiri and the Auckland Conservation Board.

Although Aotea is free of possums, mustelids and Norway rats, without current efforts to trap the ship rats, kiore and feral cats that are here other native birds would disappear – like oi (grey-faced petrels) which are still scattered around cliffs, the reintroduced toutouwai (North Island robins), and rare miromiro (tomtit), the vagrant korimako (bellbird), red-crowned kākāriki, matuku (bittern, mātātā (fernbird), mioweka (banded rail), pāteke (brown teal), tītī (Cook’s petrel), tūturiwhatu (New Zealand dotterel) and the tākoketai.

Image taken from Aotea Great Barrier Environmental Trust

The pepeketua (Hochstetter’s frog), Duvaucel’s gecko, moko kākāriki (Auckland green gecko) and the niho taniwha (chevron skink) would also be lost.

Do nothing and it is likely only kererū, tūī, pīwakawaka (fantail), riroriro (grey warbler) and tauhou (silvereye) would hang on in reduced numbers and kākā might occasionally breed or visit from Hauturu-o-Toi to target food trees. E koekoe te tūī, e ketekete te kākā, e kuku te kererū. The tūī chatters, the parrot gabbles, the wood pigeon coos … But only just.

Fortunately, the island has rallied around its native wildlife and predator control is undertaken over large parts of the island, often with generous support from Auckland Council, the Aotea Great Barrier Island Local Board and the Department of Conservation.

The Aotea Great Barrier Island Environmental Trust has advocated for restoration of the island’s biodiversity for nearly 20 years, spawning the Aotea Trap Library, the Okiwi Community Ecology Project, the annual Aotea Conservation Workshop and Aotea Bird Count. The Aotea Trap Library has over 2000 traps and boxes out around the island.

The local board broadened conservation discussion on the island in the mid-2000s and the resulting Ecology Vision website is a good place for visitors looking for information about how to get involved (https://ecologyvision.co.nz/volunteer/). Oruawharo Medlands Ecovision has caught nearly 2500 rats and mice to date in traps that are checked weekly by volunteers then recorded on the Trap.NZ database.

The benefits of sustained predator control is being seen in the island sanctuaries at Windy Hill (where more than 60,000 rats and nearly 400 feral cats have been removed over 23 years), Glenfern and Motu Kaikoura. Bird counts at Windy Hill show increasing abundance of kererū, tūī and kākā, a trend that has been reflected across the island since 2006.

The network of tracks inside 83-hectare Glenfern Sanctuary are open to the public. The regional park is enclosed in a 2km-long pest-proof fence and 800 rat traps protect populations of tākoketai, tītī, pakahā (fluttering shearwaters), kororā (little penguin), pāteke and the country’s longest skink, the niho taniwha.

The toutouwai translocated from mainland populations into Glenfern and Windy Hill in the 2000s have moved out of the sanctuaries and established a breeding population on Hirakimatā. You might see them – and miromiro, tomtits – on the tracks around Mt Heale Hut.

View over the Broken islands and to Little Barrier Island from Mount Heale Hut.

Now, with backing from the Jobs for Nature – Mahi mō te Taiao programme , Predator Free 2050 Limited, and Auckland Council, the island’s most ambitious predator free project is getting underway.

The Tū Mai Taonga project is being led by Ngāti Rehua Ngātiwai ki Aotea, after initial fundraising, the commissioning of a feasibility study and preparatory work by the Aotea Great Barrier Island Environmental Trust.

The Ngāti Rehua Ngātiwai ki Aotea Trust will now provide the vision and tikanga for the project and has appointed a sub-committee of well-connected representatives from the community to help deliver it. Tū Mai Taonga promises to create new conservation jobs and build long term hapū, community and environmental well-being.

The island is no longer satisfied occupying a middle ground. Working together it aims to bring back a full suite of seabirds and forest life, the taonga of Aotea.

Written by Tim Higham, with the support of Destination Great Barrier Island.